As a scientific discipline, archeology studies human populations and attempts to reconstitute past modes of life by the analysis of material remains. For many years, the acquisition of archaeological knowledge was carried out within a colonial perspective to the detriment of indigenous populations whose legacy is a large part of Canada’s archaeological heritage [1]1Ph.D. Thesis, Department of Anthropology, McGill University

Awakening Internalist Archaeology in the Aboriginal World

2002. With the emergence of a professional community toward the end of the nineteenth century in Canada, the foundations of the archeology became intimately connected to the moral and ethical responsibilities related to archaeological resources.

Archaeologists from the western tradition, however, generally interpret the past in a rather linear way. In addition, their interventions on the ground generally disrupt the places where the spiritual, material and sacred memories of the ancestors of the indigenous populations reside. The integration of indigenous knowledge and the active participation of indigenous communities in scientific undertakings, and, more particularly, in archeology, are recent practices [2]2Ph.D. Thesis, Department of Archaeology, University of Calgary

Quliaq tohongniaq tuunga (making histories): Towards a critical Inuvialuit archaeology in the Canadian Western Arctic

2007 [3]3Canadian Journal of Archaeology / Journal canadien d’archéologie

What Makes Us Squirm: A Critical Assessment of Community-Oriented Archaeology

2016.

The principles of a collaborative archeology include a certain degree of control of the research by indigenous communities, guidelines that meet criteria defined and developed by the communities and research objectives that integrate the knowledge and the philosophy of indigenous peoples [4]4in H.C. Wolfart (dir.), Papers of the 38th Algonquian Conference, University of Manitoba, Winnipeg

The Land as an Aspect of Cree History: Exploring Whapmagoostui Place Names

2007 [5]5Ph.D. Thesis, Department of Archaeology, Simon Fraser University

Indigenous Heritage Stewardship and the Transformation of Archaeological Practice: Two Case Studies from the Mid-Fraser Region of British Columbia

2013 [6]6Études/Inuit/Studies

Ethical foundations and principles for collaborative research with Inuit and their governments

2011 [7]7Études/Inuit/Studies

Creating space for negotiating the nature and outcomes of collaborative research projects with Aboriginal communities

2011.

The re-appropriation of cultural heritage

The adoption of the Native American Graves Protection and Repatriation Act (NAGPRA) in the United States in 1990 marked a pivotal moment in the relations between archaeologists and members of indigenous communities in North America. This law—which authorizes the analysis of archaeological discoveries, but only within a very short time-frame and only if it can be demonstrated that these analyses can make a major contribution to knowledge—, requires that the human remains, funerary objects, sacred objects and significant objects of Aboriginal heritage unearthed in the course of archaeological interventions be returned to Aboriginal populations. This legislation emerged in a period characterized by increasing self-affirmation and claims by indigenous peoples. The 1990s also saw a transformation in the relationship between archaeologists and Aboriginal communities in Canada, with a stronger commitment on behalf of Aboriginal populations to manage their own cultural heritage.

In this sense, archeology was no longer perceived as a mere instrument for the development of Aboriginal cultural heritage, but instead as a “tool” that could be used to (re)appropriate this heritage by the communities concerned [8]8Journal of the Canadian Historical Association

What We've Said Can be Proven in the Ground”: Stó:lō Sovereignty and Historical Narratives at Xá:ytem, 1990-2006

2013 [9]9Master's Thesis, Department of Anthropology, Université de Montréal

À la convergence des savoirs : la transmission des connaissances entre les Atikamekw et des archéologues

2010.

In 1996, the Canadian Archeological Association adopted, a Statement of Principles for Ethical Conduct Pertaining to Aboriginal Peoples, thus defining standards in matters regarding the consultation of the communities concerned, the participation of Aboriginal peoples, the recognition of symbolic and sacred places, and finally, communication and interpretation. Specifically, the Statement stipulates that the archaeologists must respect the cultural importance of oral history and traditional knowledge in the interpretation and development of the rich archaeological findings relating to Aboriginal peoples and to communicate the results of archaeological research to the Aboriginal communities concerned.

In Quebec, the Quebec Association of Archaeologists has adopted a Charter (amended and adopted in 2012) as well as a Code of Professional Norms and Ethics for its members, without any specifications with regards to the collaboration of Aboriginal communities in archaeological research. Collaborative archeology is more widespread among our counterparts in other provinces and territories and this practice remains embryonic in Quebec—a situation that finds expression in the meager production of francophone publications on the subject. Some initiatives have, however, emerged over the years often taking the form of Aboriginal communities assuming responsibility for archaeological research in collaboration with non-Aboriginal archaeologists.

The applications of collaborative archeology

It is obvious that greater collaboration between archaeologists and Aboriginal communities is desirable and should be encouraged. But this participatory collaboration must have clear guidelines. The objectives of a collaborative archaeological research project must be clearly defined by the different stakeholders. In addition, the results of archaeological interventions and the interpretation of data may run counter to some expectations and may even be detrimental to the Aboriginal communities concerned. There is therefore a raising of awareness to be done in this respect, not only with regards to the general public, the media and the governmental agencies concerned, but also with regards to the archaeological and museum communities [3]3Canadian Journal of Archaeology / Journal canadien d’archéologie

What Makes Us Squirm: A Critical Assessment of Community-Oriented Archaeology

2016 [10]10Ph.D. Thesis, Department of Archaeology, Université Laval

L’archéomuséologie : un modèle conceptuel interdisciplinaire

2005 [11]11Cap-aux-Diamants

Une discipline pour des passionnés : l’archéologie québécoise d’hier à aujourd’hui

1999.

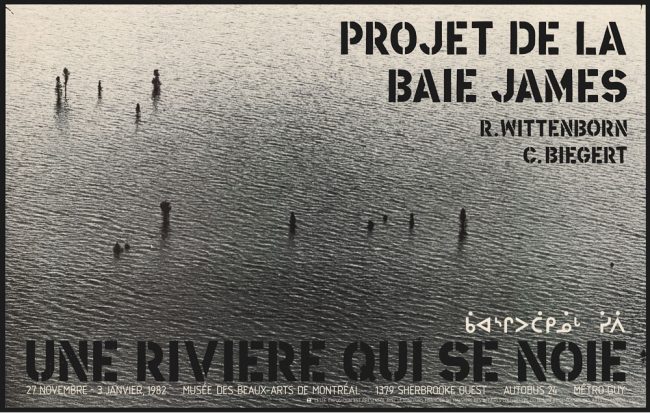

In Quebec, the expansion of the archeology has been closely linked to the establishment of the James Bay hydroelectric project in the 1970s, in particular with regards to environmental impact studies [5]5Ph.D. Thesis, Department of Archaeology, Simon Fraser University

Indigenous Heritage Stewardship and the Transformation of Archaeological Practice: Two Case Studies from the Mid-Fraser Region of British Columbia

2013. Even though the integration of members of some northern communities, including the Cree and the Inuit, into teams of archaeologists began during this period, in the short term, the collaboration was more beneficial for the latter.

Let us briefly consider a few examples of collaborative archeology in Quebec, Nunavik and British Columbia where, over the years, a true partnership has developed:

> The methodological approach favored by the Cree Nation Government (formerly known as the Cree Regional Authority) is an excellent example of taking charge of an archaeological heritage and the integration of traditional knowledge where the fundamental component of the enterprise has been to use the knowledge of elders as the point of departure for archaeological research and in the identification of sites of archaeological interest [4]4in H.C. Wolfart (dir.), Papers of the 38th Algonquian Conference, University of Manitoba, Winnipeg

The Land as an Aspect of Cree History: Exploring Whapmagoostui Place Names

2007 [12]12Continuité

Patrimoine cri : savoirs du Nord

2002.

> The program of Community Archeology with the Inuit of Nunavik in the Avataq Cultural Institute. The Department of Archeology of the Avataq Cultural Institute is mandated by the Conference of the Inuit Elders of Nunavik to identify, study, protect and preserve the archaeological heritage of Nunavik. The activities of the Institute enable young Inuit to participate actively in archaeological research conducted in Nunavik. Since its foundation in 1985, many archaeological research projects have been conducted with the Inuit – including Sivunitsatinnut ilinniapunga, “for our future, I am going to school”—which organizes activities related to excavation Field Schools.

> The archaeological project Sq’éwlets (1992-1999) was the result of a partnership between the members of the Sq’éwlets Community, the Stó:lō Nation and archaeologists from the University of British Columbia and Simon Fraser University. In addition to enabling the acquisition of knowledge on the history of the Sq’éwlets, this project has helped to develop different resources such as traditional knowledge labels as well as linguistic and educational resources.

> The project Intellectual Property Issues in Cultural Heritage (IPinCH) developed by George P. Nicholas (Simon Fraser University) in collaboration with Julie Hollowell (Indiana University) and Kelly Banister (University of Victoria) promotes a model of collaborative research that fosters the empowerment and protection of indigenous communities while contributing to the enrichment of university research. In 2014, a resolution entitled Declaration on the Safeguarding of Indigenous Ancestral Burial Grounds as Sacred Sites and Cultural Landscapes was proposed within the framework of this project by nearly 30 professionals (anthropologists, archaeologists, lawyers, representatives of aboriginal communities). In the year that followed, this principle was endorsed by more than a hundred professionals, researchers, organizations and associations in different countries in North America, Europe and Africa.

Translation: Peter Keating